On This Campus, Every Student Could Join a Union. The College Calls It an ‘Existential Threat.’

Student workers at Berea College won’t be the first undergraduates to unionize, but a union at this small Kentucky institution would be a first in other ways.

If successful, it would be the first of its kind in the South, a region that’s historically been anti-union. It would be the first student-worker union at a federal work college, where students hold a job in return for free tuition. And it would also be the first undergraduate union to count every student on campus as a member.

Berea is a “historic and important place” in American higher education, said Timothy R. Cain, a professor of higher education at the University of Georgia. A unionization effort there “speaks to in some ways the larger conditions of work in higher education,” Cain said.

The college, which serves around 1,400 students, most of them from low-income families, has made its name on promoting equity. But some Berea students say the college’s model does not extend that equity to its workplaces.

Across the country, recent unionization efforts have pushed colleges to rethink their relationships with student workers, a longstanding source of inexpensive labor in dining halls, dorms, and elsewhere on campus. That’s an especially pressing debate at Berea, an institution that relies heavily on student labor to function.

As administrators see it, the prospect of unionization cuts deep into the college’s identity and status. “We have a mission unlike any other in this country,” said Chad Berry, Berea’s vice president for alumni, communications, and philanthropy. The prospect of a student-worker union is an “existential threat to that mission” and to Berea’s continuation as a work college, Berry said.

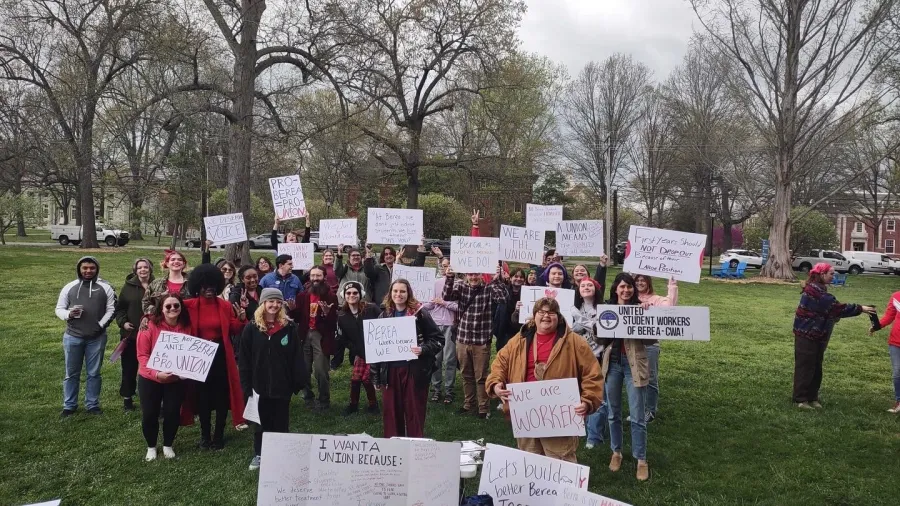

According to the union organizers, a majority of Berea’s student workers submitted signatures to the National Labor Relations Board in March and asked to hold a union election, which the college has contested. The NLRB is expected to rule in the coming weeks on whether to allow the election to proceed.

A New Legal Landscape

The Berea case distills the legal battle over how to define student workers to its purest form.

Student workers at private colleges gained the right to unionize after a 2016 NLRB decision that established that they were employees. The Berea case may test the limits of that ruling, because the college’s unique model incorporates work into its educational mission, and students are paid with scholarship funds.

The test the NLRB established in 2016 was to look at “whether the college controls the employees’ work and whether they perform that work in return for compensation,” said William A. Herbert, executive director of the National Center for Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College, part of the City University of New York.

If that test is met, students can negotiate with the college over their compensation, regardless of what form it takes, Herbert said.

Unlike other work colleges, Berea distributes “work direct payments” for hourly labor in addition to free tuition. The college emphasized that the payments are tax-free financial aid, and not employee wages. The payments are typically below minimum wage and can only be used for educational expenses.

Berea has described the student payments as “wages” in the past, but that language has largely disappeared from the college’s recent communications, said Andi Mellon, a student farm worker who circulated a petition in 2022 that called for student workers to be paid federal minimum wage.

Securing better pay for workers on campus would be a bargaining priority for any future union, Mellon said, but “it’s a mistake to focus entirely on pay.” If pay is off the table, “then that’s what it is. But we don’t know that until we sit down at the bargaining table and talk about it.”

Students who spoke with The Chronicle also see unionizing as a way to improve working conditions, hold managers accountable, and create better processes for reporting workplace discrimination.

Cheryl L. Nixon, president of Berea College, has written extensive updates on the unionization effort. She wrote in one of many public letters that a union would be “structurally incompatible” with Berea’s model.

Nixon said if the NLRB defined Berea students as employees who receive wages, it would set up an “unprecedented conflict” with the U.S. Education Department, which defines Berea students as students who receive scholarships. She said that the college already awards students 100 percent of their financial-aid packages and therefore would be unable to increase their pay. An Education Department spokesperson declined to comment.

Students pushed back against the idea that a union would run counter to Berea’s identity. “Students would not be organizing for better conditions if we did not care deeply about this college and the community,” Mellon said. Forming a union would be an expression of that care, they said.

Students said the union would also fit into the college’s educational mission. These days, unions are a part of many workplaces, said Cora House, a student worker at a campus service center, and learning to negotiate a contract is a valuable skill. Students graduate from Berea and enter difficult workplaces where “they don’t know how to ask for more,” Mellon said.

A Undergrad Union Wave

The sheer fact of a credible undergraduate-unionization effort at a work college in the South is a testament to the energy of student-worker organizing, labor experts said.

The movement was first concentrated at elite private universities in the Northeast before more recently shifting to large public universities in the West.

Now efforts are underway to form undergraduate-worker units at Kenyon College, in Ohio, Macalester College, in Minnesota, and Occidental College, in Los Angeles. Dining-hall workers at the University of California at Santa Barbara and Syracuse University are organizing, and undergraduate workers at the New School, in New York City, and Western and Central Washington Universities are vying to join their campuses’ graduate-worker unions.

The undergraduate-union movement could influence collective-bargaining efforts in other industries, said Joseph Van Der Naald, a research fellow with the CUNY National Center. The unit being organized at Berea would be a “wall-to-wall” unit, which means it would represent student workers across campus regardless of their job or department. This is a remarkable development, Van Der Naald said, “because so much of the American labor movement has been stratified by occupation.”

A majority of undergraduate-worker unions today are not wall-to-wall, but most of the pending union efforts are using that approach. The California State University system’s wall-to-wall undergraduate union was certified last month, representing more workers than all other similar unions combined.

Berea’s student-worker union would take the concept of a wall-to-wall unit one step further, because it would include every student at the college. That could give the union more leverage in negotiations with administrators.

Lily Barnette, the Berea Student Government Association president, a paid position that the union would represent, said at the end of the day “the college administration doesn’t have to listen” to the student government. But a union would have the leverage and legal authority to negotiate binding agreements.

If Berea student workers get the NLRB’s go-ahead to hold a union election, that’s only the first step in a long process. The real challenge, Van Der Naald said, is to negotiate a contract.

In April, the student-worker union at Grinnell College, in Iowa, became the first wall-to-wall undergraduate union to sign a contract with its college after more than two years of intense negotiation, dueling unfair labor-practice suits, and one strike. Right now, student workers at the California State University system and the University of Oregon are negotiating their first contracts.

Van Der Naald said that before the post-pandemic upswing in student unionizing, he would have been unsure if Berea student workers’ could succeed in their effort. Today, though, things are different. After the “explosive” growth in undergraduate unions across the country, “the chances of this union being successful in their representation election are good,” he said.

This article was originally published in The Chronicle of Higher Education on May 14, 2024.